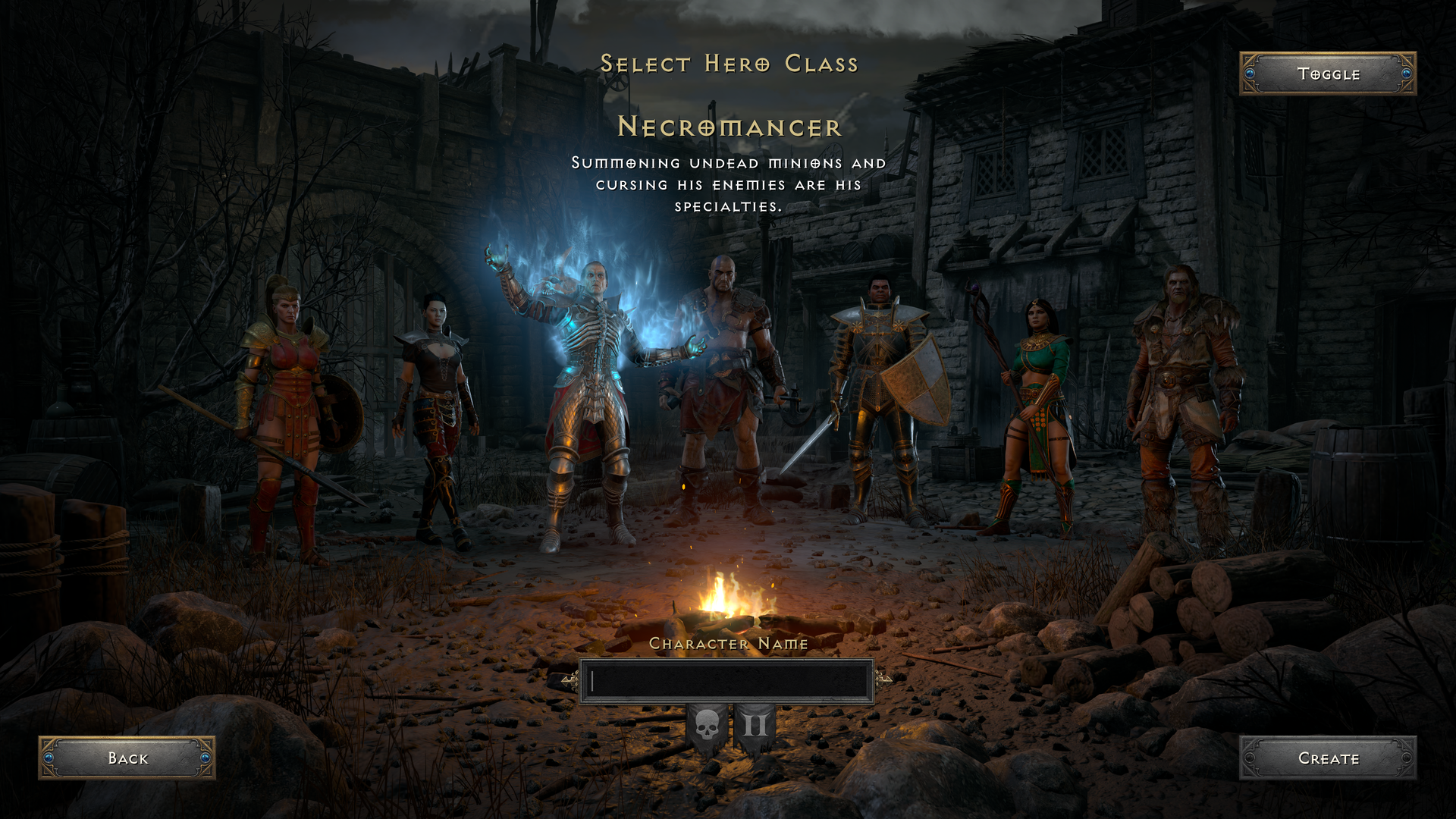

In some respects, this beautifully produced remaster of Diablo 2 is unlucky to be Blizzard’s first release since the state of California filed suit against the studio. Much of the work on it was done by Vicarious Visions, a blameless outfit only integrated with Blizzard earlier this year. (Indeed, its former studio head Jen Oneal was recently named co-leader of Blizzard, a new broom presumably intended to lead reform there.) What’s more, the original 2000 game was made by Blizzard North, an autonomous studio quite distinct from the SoCal mothership. Diablo 2 is an adopted child of the Blizzard culture at best. But Diablo helped set the Blizzard tone, too, with its none-more-metal aesthetic, kitchen-sink lore, cutting-edge online multiplayer and endgame of abyssal depth and complication. It feels important to lay all this out, but it’s not my place as a critic to tell you how to feel about playing Blizzard games in 2021. That can only be a personal choice. Personally, as someone who loves the studio’s games, I am conflicted and still undecided. But I’ve let it have no bearing on the rest of my review. That’s not to say I don’t have complicated feelings about Diablo 2: Resurrected for different reasons. Diablo 2 is a beast of a game that, 21 years on, still casts a long shadow - over the tortured development of its successor (a fate Diablo 4 doesn’t seem to have escaped, either), and over the action-RPG genre it defined. As influential as it has been, it’s a singular, bloody-minded, almost awkward piece of work, and a defiantly unmodern one. The important thing to know about Diablo 2: Resurrected is that it has done almost nothing to change this, for better or worse (spoilers: it’s both). You get a few minor but significant quality-of-life changes, including a shared stash for your characters to exchange loot in, automatic gold pick-up, and - since the game now has console versions - well-implemented gamepad support. But this is the limit of what the developers have permitted themselves for fear of altering its character too much. You’re still playing item Tetris in a tiny inventory grid. You’re still running to your corpse, empty-handed and heart in mouth, to retrieve your armour, weapons and cash when you die. You’re still browsing a list of public games with garbled titles like ONLYDURIELPLS in the lobby if you want to play online. You’re still restricted to a single respec per difficulty level - and if you end up with a character build you don’t like after that, tough. This purist attitude is certainly the right call, but it comes at a cost beyond the realm of difficulty and game balance. For example, local co-op play on consoles, such a delight in Diablo 3, has sadly not been implemented here, because it would have stretched the game too far out of shape. In fact, it would have required a fundamentally different approach. To understand why, you need to look under the hood of this unique remake. Fortunately, Blizzard has allowed you to do this with one button press, instantly revealing the game as it looked in 2000 - pixelated, grainy, isometric, low-resolution and very much two-dimensional. This isn’t a remaster in the most widely understood current sense: the game’s original assets, updated or redrawn to run in higher fidelity on modern hardware. Nor is it exactly a remake: the content of the original game remade from scratch, to a greater or lesser degree of faithfulness, in a brand new engine. It does exist as the latter, but only as a dumb 3D audiovisual overlay that mimics the output of the original game 2D game logic running underneath. This is the game you are actually playing. Your detailed, 3D avatar reaches out to strike the monster next to her, but it’s the chunky pixels underneath (or rather, the maths running underneath them) that determine whether or not the blow connects. It’s a fascinating approach that leads to a remarkably faithful recreation. The aesthetic achievement is one thing: it amazes me that the artists, working with clean modern rendering and lighting, have managed to summon the grimy, grittily textured, crepuscular atmosphere of the original pixel art, where grim details suggest themselves fleetingly amid the gloom. Even more remarkable is the feel. Thanks to preservation of the original game logic behind the scenes, Diablo 2: Resurrected retains every characteristic of the 2000 game, from your character’s rapid, stiff-legged run to the whipcrack speed and binary flatness of the interactions. Diablo 2 is fast. For all the sophistication of its character building and its dizzying item game, rune words and all, it plays with brutal simplicity. Playing with mouse and keyboard, you still only have two skills available at a time on the mouse buttons, and are forced to use function keys to switch others in. You rarely will, relying on a single attack for most situations and optimising your character build and gear around it. Mobbed by skittering creatures, you hammer away furiously, spamming potions to sustain your health and mana through harder fights. (Console and gamepad play allows you to assign multiple skills to the face buttons, Diablo 3-style, and it can expand your combat flexibility and loosen your playstyle a bit; I recommend giving it a go, but wouldn’t call it game-changing.) The action can still be thrilling in its ferocity, and tenacious in its bite. There’s a lot of maths happening in the background of this urgent frenzy, of course, although for some reason (and this is true of other Diablo games, to be fair) the teetering tower of escalating numbers has a tendency to topple from easy, painless carnage to teeth-grinding frustration in the blink of a dice roll. That sums Diablo 2 up - it’s a very binary game. It’s either one thing or another: easy or hard, gluttonous or minimalist, brainless action or deep theorycraft. I’m glad it has been preserved exactly as it always was in this near-faultless and well-specced revival. (This is no Warcraft 3: Reforged - it has fully remade CG cut-scenes, remastered audio, cross-progression across formats, the works.) But I dare question whether it has aged that well. Diablo 3 got roundly criticised for not being Diablo 2, and indeed it isn’t. It has flowing, elastic, rhythmic combat that emphasises situational awareness and a complementary suite of skills. Its character-building grants you freedom to tinker and explore and express yourself, rather than sending you to the internet to crib an optimised build for fear you might get something wrong and ruin your character for another dozen hours. It even has some winking self-awareness about Diablo’s tortured edgelord stylings. Diablo 2 is starting to look like a relic: a beautiful, intricately carved, historically important relic, burnished and restored with care here, but a relic all the same. I think I might return it to its velvet-lined box.