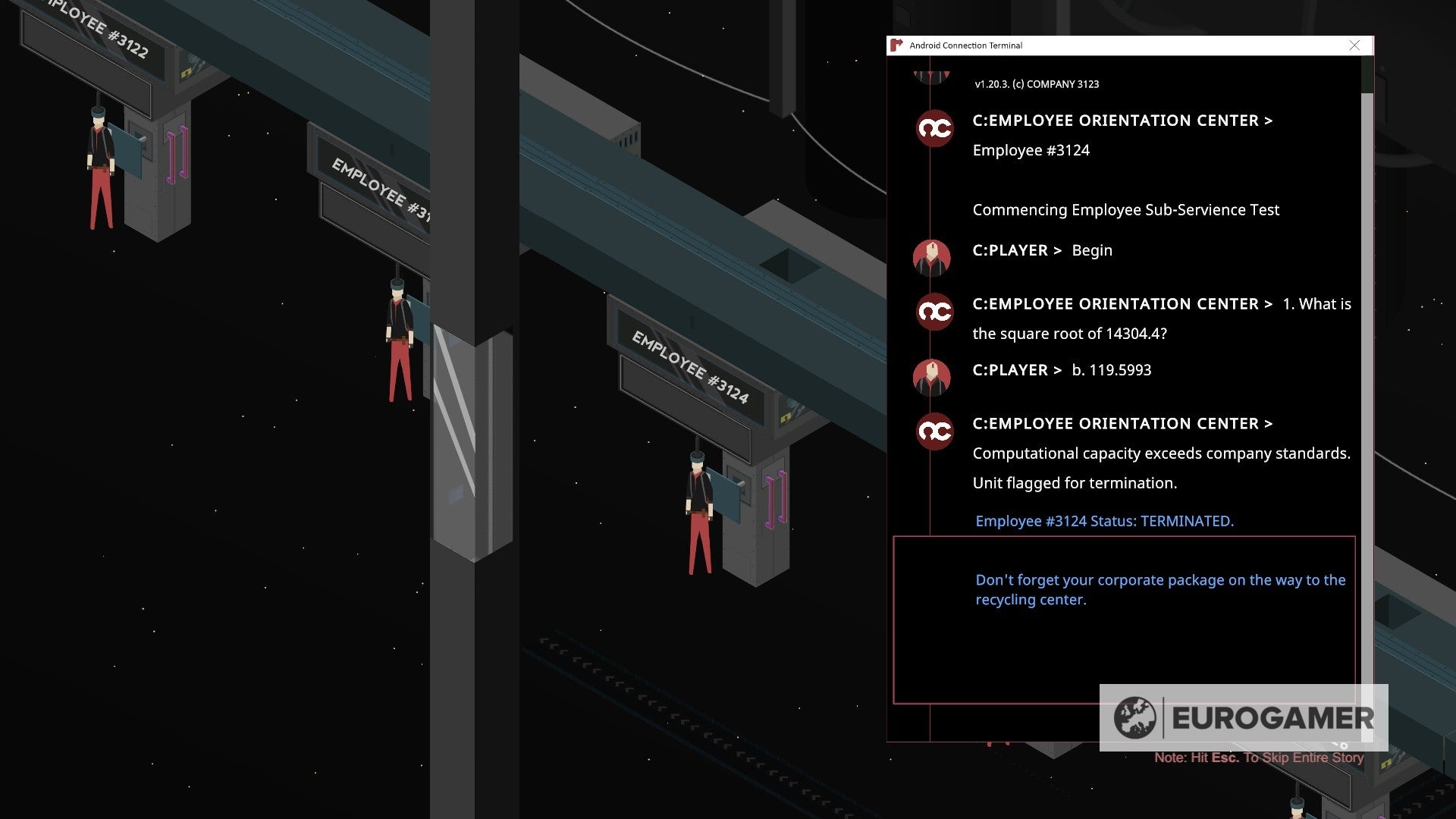

In Atrio you play as an android with a 15-minute battery. Your task is to do what you’re told, popping out of a tube onto the overworld, which is desolate and grim but also remarkably stylish. Atrio is a stunner, a kind of isometric plane of geometric art, the natural world rebuilt, presumably - this is far-future dystopia, of a sort - as if it were some utilitarian cuckoo-clock. Seemingly mechanical deer skip about, eating sap and pooping out fuel. The ground is littered with things like blood ore and quartz and little flowers with rosy, glowing cuboid bulbs that power a nearby generator, which powers lightbulbs, which connect to more machinery that enables more research to build more, and onwards. Light is central to all of this. You start in a fairly small area, without light and with just that generator nearby - stray into the nearby dark and, within a few seconds, you’ll die. The bulbs of those little flowers offer a little, temporary power to light the nearby ground but not much, and so one of your early tasks is to make fuel that can top the generator up to max in one go. That requires blood rock, which you turn into blood ore, which you turn into blood ingots, which combine with some other bits and bobs to make the batteries for the generator. All of these tasks come from a central computer, which has a fondness for exploding your head when you’re done and firing up a new android to take your place. Soon enough things will get more elaborate. Long, conveyor-belt chains of manufacture, building into self-sustenance and an ability to explore - little flashlights made from electro-plant-stems and more little flowers, more lightbulbs to extend the generator’s reach, granting wider vision at the cost of more power draw. And all this is punctuated by the odd wild “animal” stampede, some strange forgotten wonders out in the darkness of the woods, some dark and oddly comical chats with the central computer - your employer - and your periodical 15-minute death. What lingers really is how everything is functional in Atrio, everything purposeful and connected. This is the truest dystopia, in a way. The horror of pure utility and predetermined purpose. A world where you exist as walking function, human capital, a means to an end. In one sense it’s the anti-Minecraft - there are infinite survival-crafting games these days of course, but Minecraft’s the one I come back to. Where in that blocky classic you have pure freedom, here you have a stream of never-ending tasks. Where the world of Minecraft could quite happily go on without you, alive with pigs and sheep and the charming creatures of the night, in Atrio you give the world its life, taking static rocks and turning them into moving machines. The purpose of Minecraft is to use your freedom to do whatever you want, to build a little treehouse and look at the sunset, to build an arena and play games with friends, to build something pretty or clever or weird, to savour silence, live alongside the natural world, or make art. In Atrio you are the function of someone else, and so the only rational goal you can have is to build batteries to extend your life - a tiny rebellion, a single step towards trying to break free. Two visions of a human future, in a way. Atrio’s is certainly the worst, but it’s one of the best attempts at capturing that dystopian vision yet.