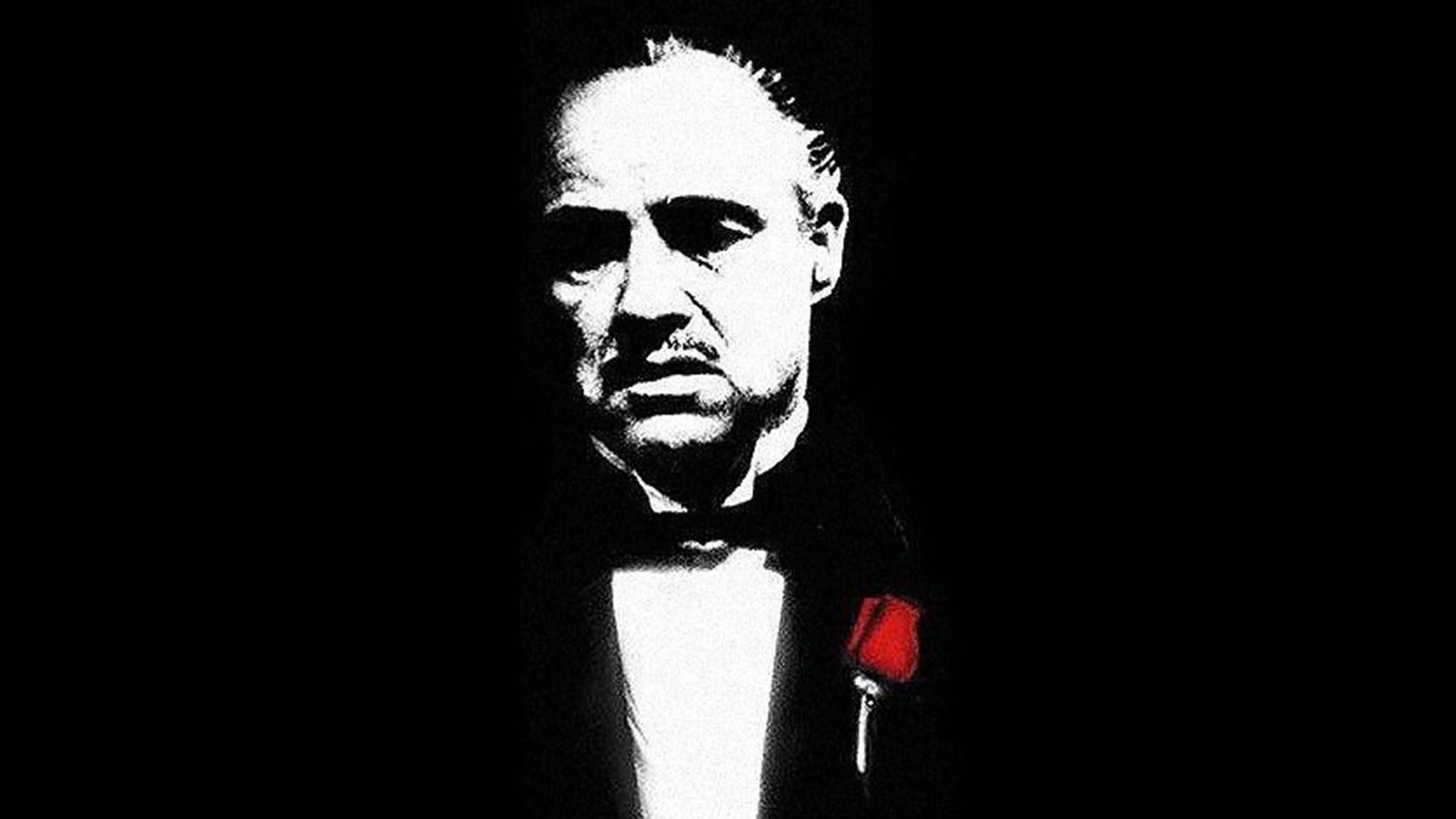

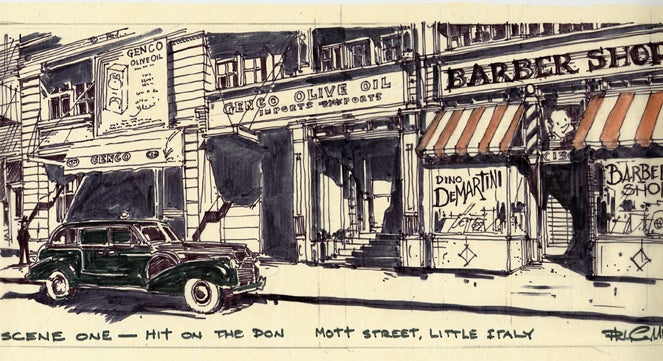

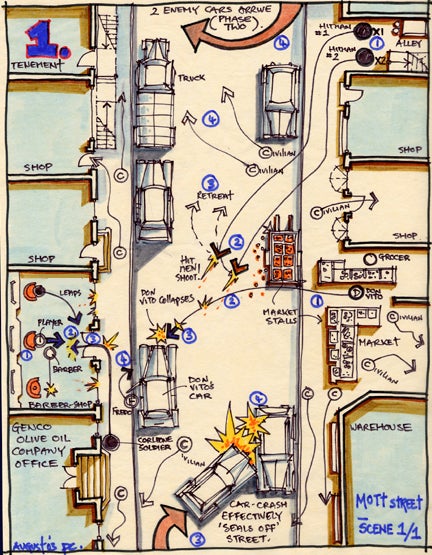

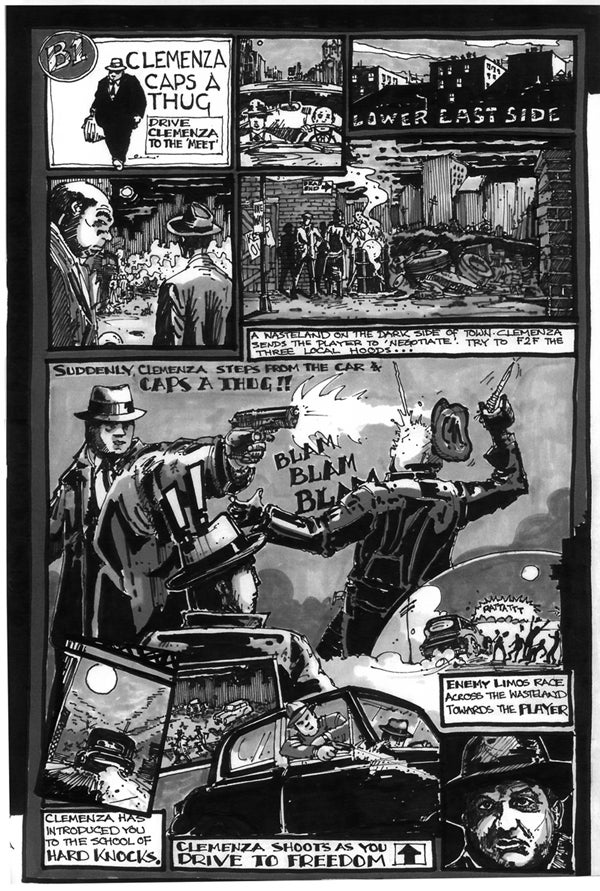

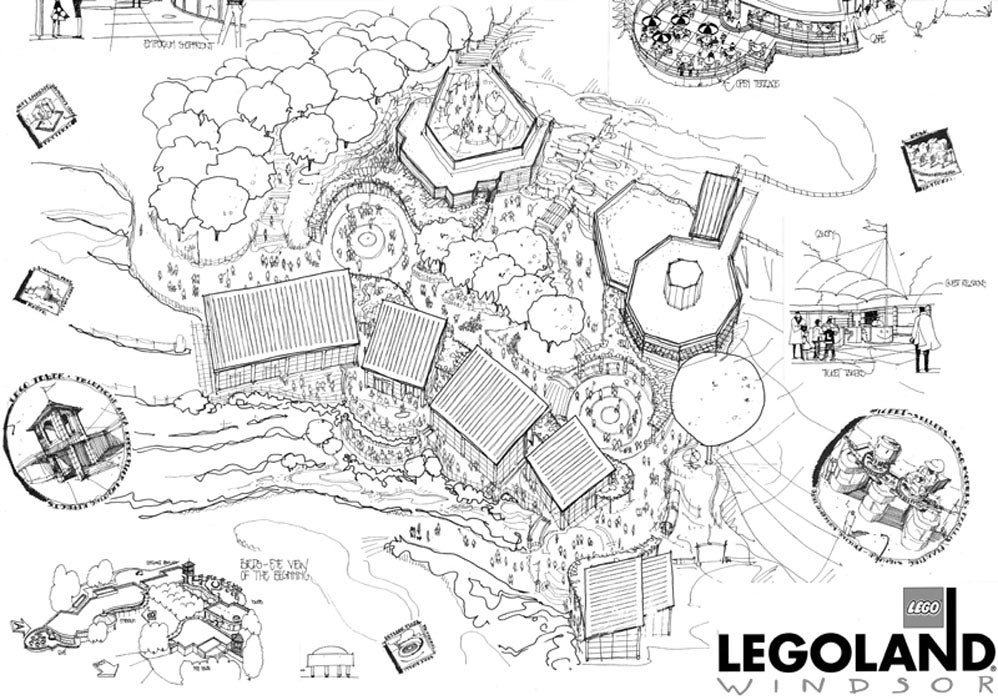

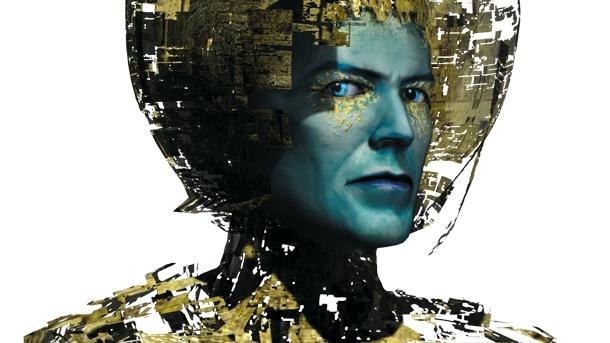

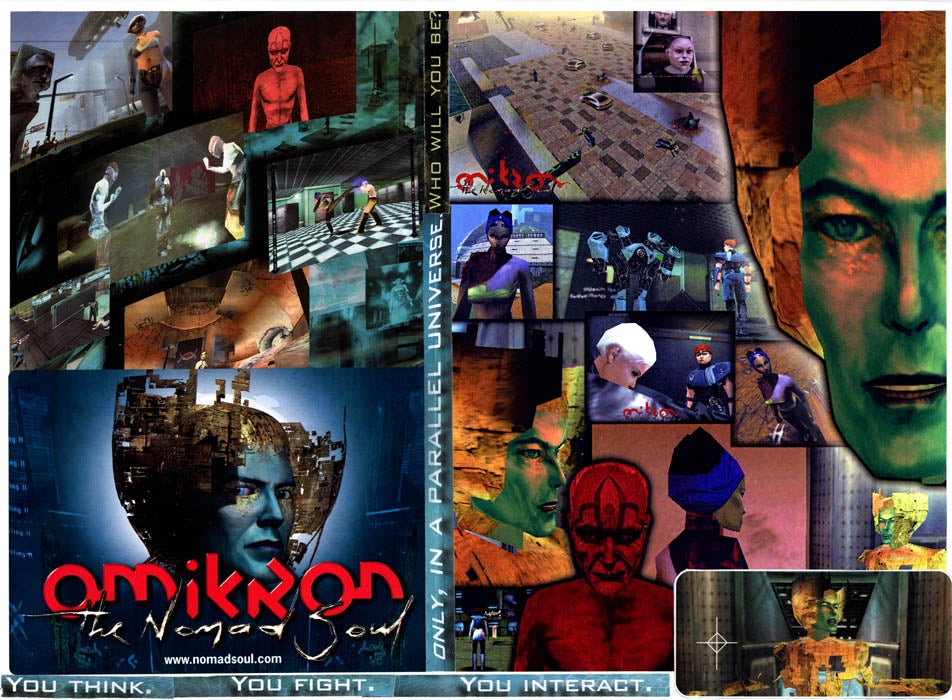

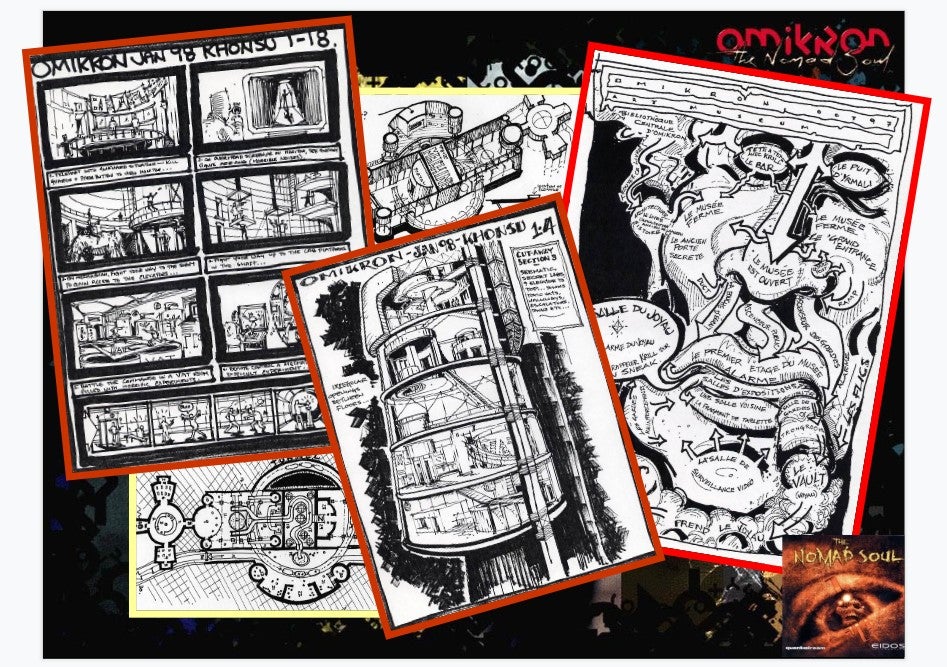

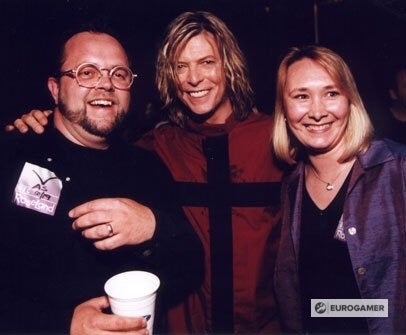

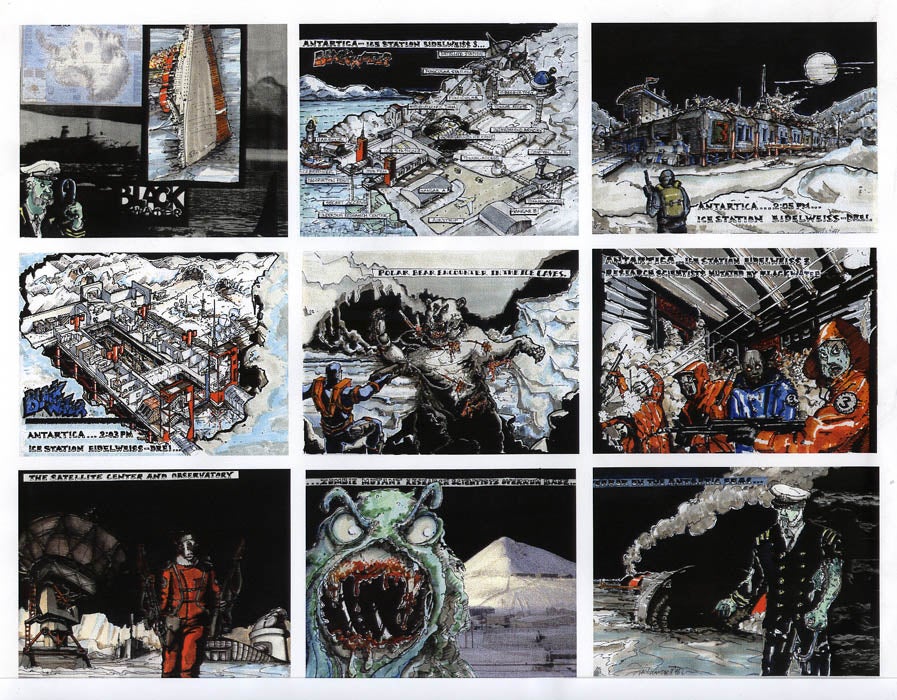

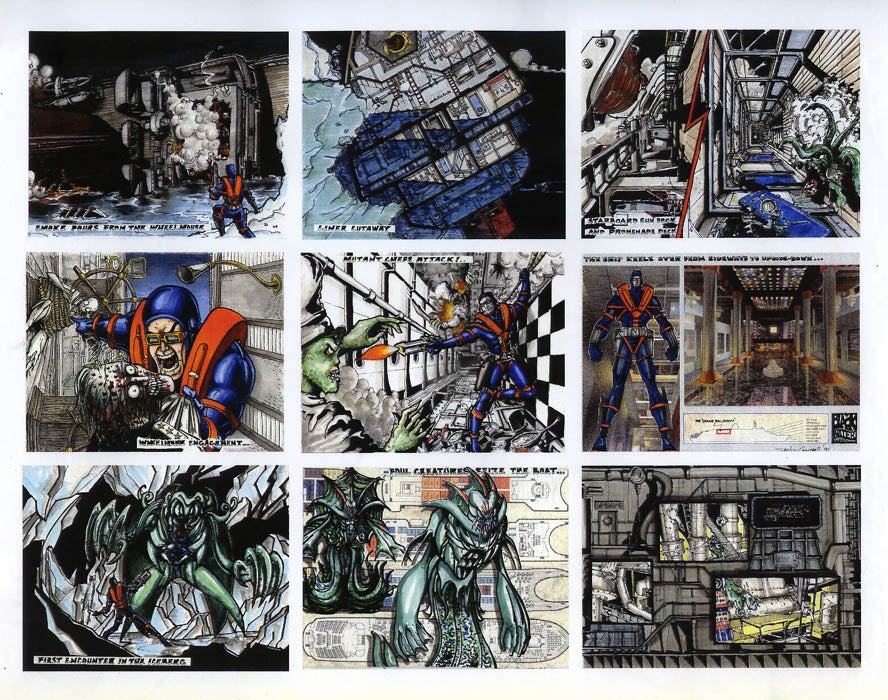

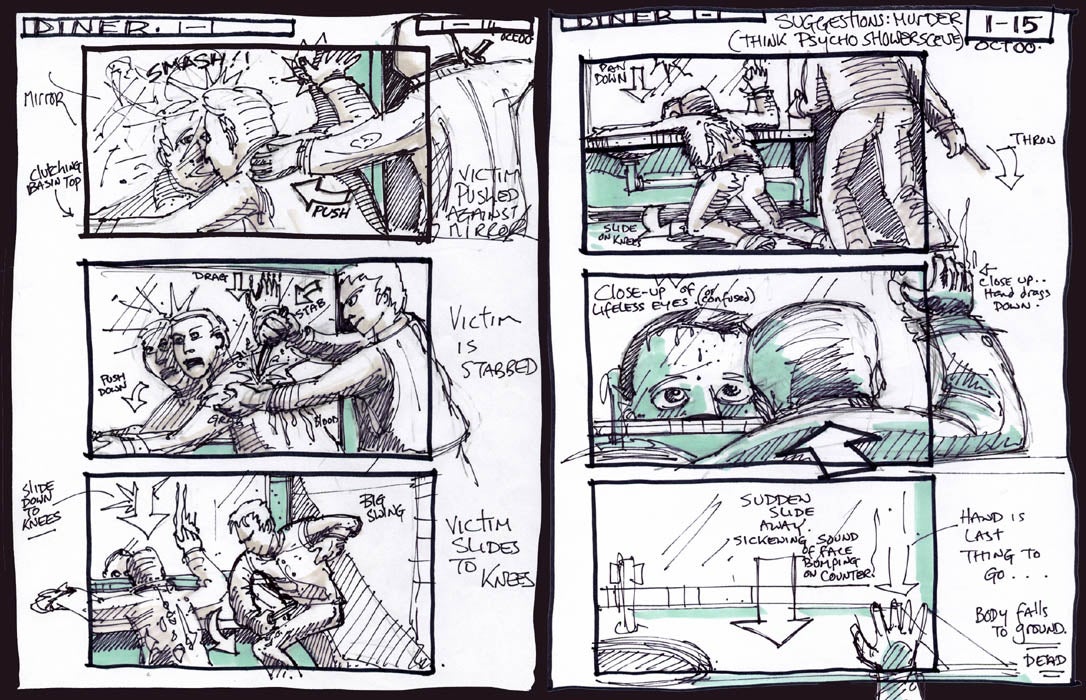

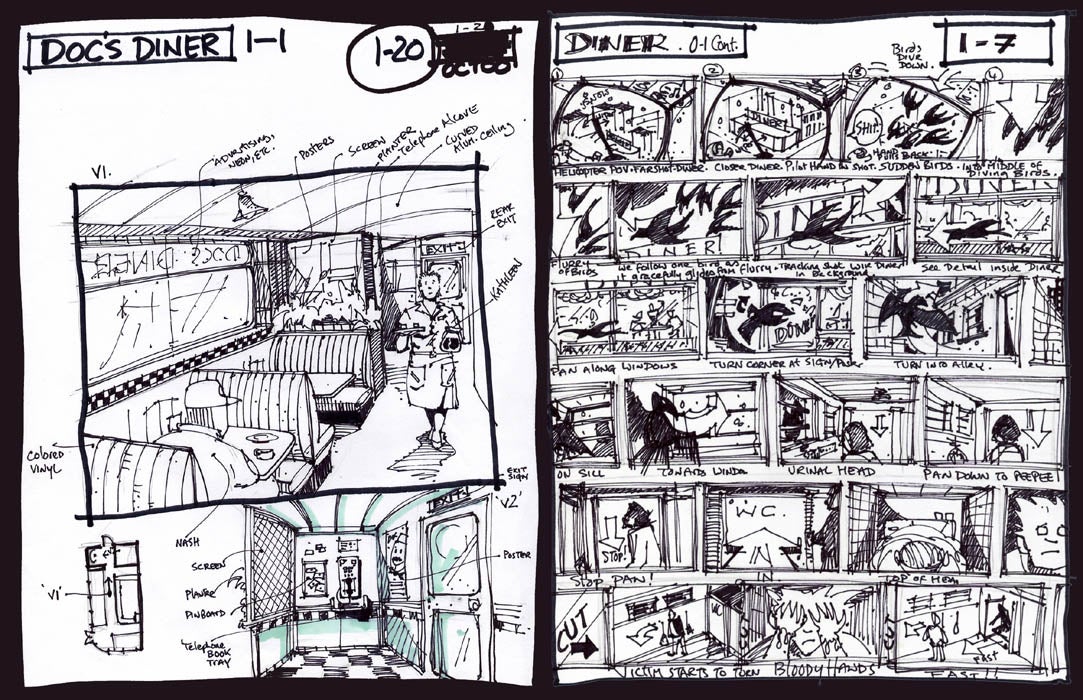

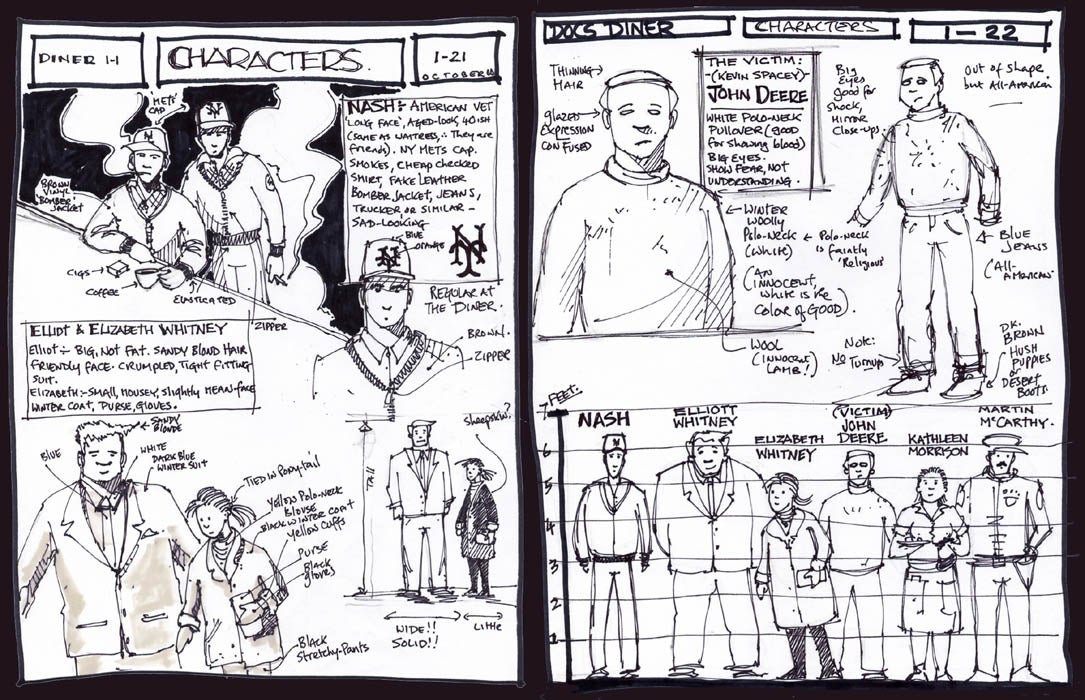

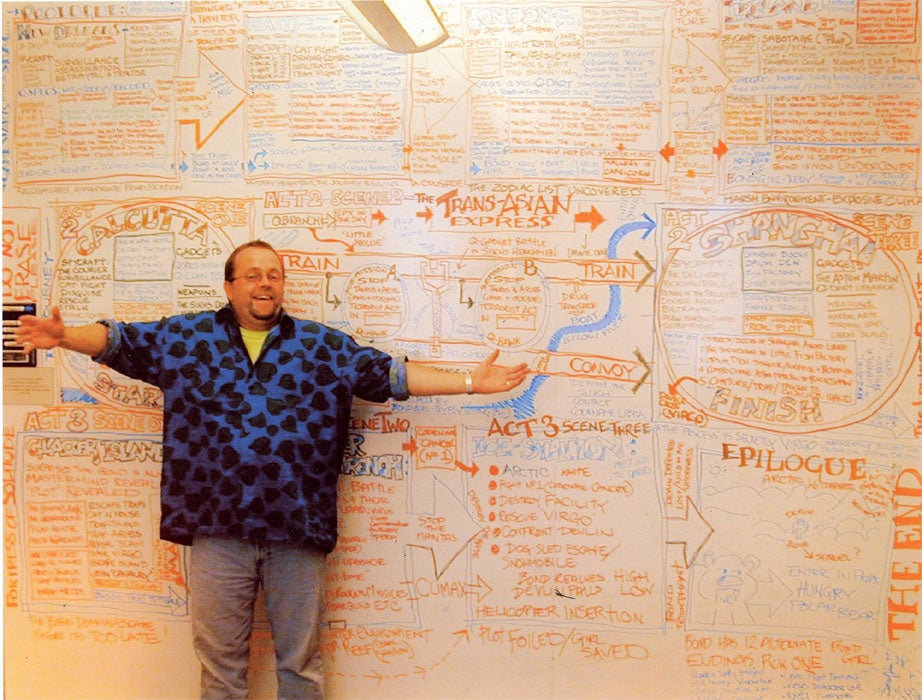

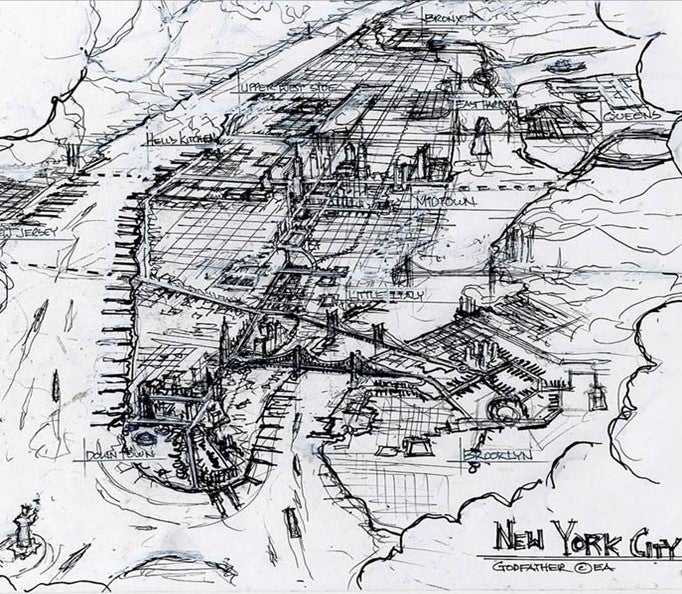

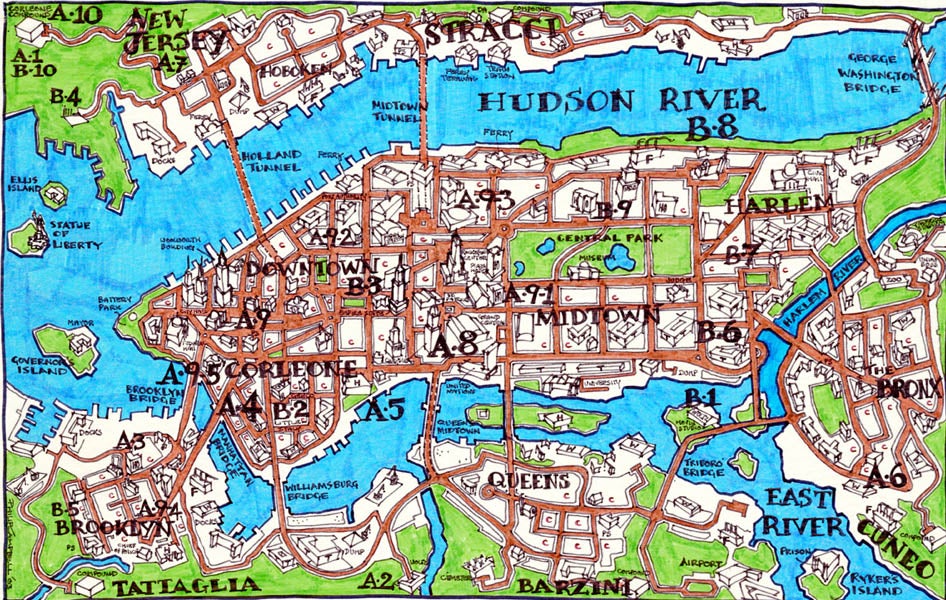

You’d better sit up straight. Meet Phil Campbell, a guy you’ve probably never heard of. But you’ve probably played his games and you’ll definitely know the people he’s met. He’s got stories for days. This is one of them. In June 2004, Campbell was in a car with Godfather executive producer David DeMartini, on the way to Marlon Brando’s Hollywood home. Brando couldn’t make it to a recording studio because he wasn’t a well man, but EA had made him an offer he couldn’t refuse so they would go to him instead. The deal was for two recording sessions over two days - one now, one in the future, both around four hours long. They pulled into Mulholland Drive and buzzed the gates. In the backseat was a basket of fruits and wines to sweeten Brando up. “He’s quite the connoisseur,” Campbell tells me. But the gates to the house wouldn’t open. Even then, with the deal shaken on, “He tried not to let us in,” Campbell says. Phone calls were made, lawyers talked and eventually the gates clicked open. “It was just like a regular house but it had grounds,” Campbell recalls. “I remember when they let us in the security gate we came up through fields and grounds, and there was landscape gardeners and people working.” Jack Nicholson lived next door. “I could have hopped the fence!” Then, Brando. The actor with a mountain-like presence. The actor who’d defied Oscar awards in the name of activism and turned televised interviews on his hosts. And all of a sudden, the idea of ‘chatting for a bit to get to know each other’ didn’t seem so straightforward. But down they sat, with the recorder on - Campbell recorded everything - and began. “You know, there’s an incredible self-intimidation factor with Brando,” Campbell says, “and for the first while - you can hear it in our conversation - he’s strong.” Brando is holding court. He’s making phone calls in “two or three different languages” and regaling the visitors with tales from his decorated past. “At one point,” says Campbell, “he was telling us a story about [Elia] Kazan [director of On the Waterfront] and he actually did the scene from the back of the taxi cab, the contender scene, and we couldn’t believe our ears, our jaws were dropping. He was doing it to make a point about everyone considering it an amazing piece of acting, and he was saying it wasn’t, really, it was his audience that generated that impression. “He was charming,” he says. “We chatted for so long with him.” Eventually, it came time for Brando to clear everyone out of the room and get down to business, everyone except Campbell and a sound engineer hidden around the corner. Marlon Brando and Phil Campbell, more or less alone in a room Campbell believes “some stuff had gone down” with Brando’s troubled son. All Campbell had to do was hand over the script he’d written and direct Brando’s performance of it - no biggie. “And of course, at first, when you’re dealing with Marlon Brando, you tend not to butt in or correct or anything, but over the course of time he made it obvious I could interject and feedback, so I did try to get a performance out of him,” he says. But there was a problem. They had worn him out. “We chatted for so long with him, it probably tired him out,” Campbell says. He had a breathing tube, Brando, and their one shot at overcoming the audio quality issues with it, was to muster a really big performance. But he hadn’t the energy. “If it wasn’t for the really bad audio quality, he actually did it really well,” Campbell assures me. “He took us back to the whole Godfather thing.” But they couldn’t use it. And they never got the chance to try again. Two weeks later, on 1st July 2004, Marlon Brando died of heart failure, aged 80 years old. “It was, in fact, the last script he ever performed.” But all was not lost. Yes, the many grandfatherly talks Campbell had primed Brando for would not be recorded, and an impersonator would have to step in, but some Brando did make it into the game. Go to the hospital, says Campbell. “If you go and lean in, by [Don Vito Corleone’s] room, you can hear the real Brando.” Campbell’s dad was a well known architect. He made a name for himself designing modern movement-influenced houses in the ’50s. “All of his houses are now listed as of historical significance and you can still see them around the north of Ireland,” Campbell says. “I always dreamed of buying one of them.” But teenage Campbell didn’t want to be an architect, he wanted to be a punk, so in 1976 he joined a band called Pipeline as their singer. You might have heard of them. “We have the honour of being mentioned on the internet once,” he jokes, “when we supported the Undertones at the Portrush Arcadia.” Being a punk offered an escape from the bloody Troubles in Northern Ireland, which Phil Campbell grew up in. “The great thing about being a punk rocker during The Troubles,” he says, “was that there was no religious divide for us - protestants and catholics hated us alike! “I suppose it was a bit of an escape. We would go to the seemingly most dangerous places in Belfast and Derry just to see great bands. In Belfast, Stiff Little Fingers, the Outcasts and Rudi were all getting going. In Derry, we took our fear in our hands and ventured to see the Undertones at a tiny pub called the Casbah…” But the punk rocker dream didn’t last. “This was never a feasible career for me,” he says. “I was a terrible singer.” And the pull of architecture was too strong. But again, there was a problem. “I don’t know if this is publishable…” Campbell begins. “I always remember being called into an executive meeting for The Godfather and they had my script for Sonny in front of them - I used to do these really nice packages with lots of drawings and images. “They called me into this meeting, these producers, and they said, ‘Look, we’ve gone through your script for Sonny and there’s too many “fucks” per page. I’d like you to take out two “fucks” per page.’ And so, after moaning and whinging about it - basically a creative director’s job - I proceeded to do that.” Cue James Caan. “He hadn’t changed at all,” Campbell says. He was Sonny Corleone. It was like he never left the role. And when you have an actor so in the moment, you let them improvise, you roll with it - no matter what comes out of their mouth. And quite a lot did come out of Caan’s mouth, much to the executive’s displeasure and Campbell’s delight. “He actually added back about four more ‘fucks’ per page,” Campbell says, laughing. “It was very satisfying. It was actually one of my most satisfying moments. He added imaginative swears I never could have written.” Such as? “Well,” he answers, “some of them were in Italian and they may have referred to certain parts of a horse’s anatomy…” He laughs. “It was classic. They’re all in the game.” Alongside Caan, EA convinced Robert Duvall to be Tom Hagen again, and sought impersonation permission from the estates of actors no longer alive. But there was a notable exception, an actor who both refused to be in the game and refused to be impersonated: Al Pacino, who played Michael Corleone. On the surface, Pacino’s refusal was understandable. “He wasn’t bad about it, he just said he created his legacy with The Godfather and he didn’t want to go back to it, he didn’t want to change it,” Campbell says. “That was hard to take but he was perfectly reasonable.” But why, then, did Pacino agree to be impersonated in Vivendi’s Scarface game, released only a few months later? He even apparently handpicked the voice actor (Andre Sogliuzzo) who would be Tony Montana in the game. Did Vivendi offer Pacino more money? Or was Scarface not as important to him as The Godfather? Campbell consoled himself with the latter. “That’s the way we read it.” What hurt more than Pacino, however, was what happened with Francis Ford Coppola, who directed The Godfather films. Contrary to popular belief, he was involved, at least to begin with, before he decided to pull out and pillory the game. “We had Francis Ford Coppola on board until he decided to trash us in the press,” Campbell says. “He came around, with his entourage. We showed him some early cuts and a whole bunch of stuff.” Coppola even invited the game-makers to his private archives. “I actually got to play with that amazing script he doctored,” says Campbell. “It’s a really legendary movie document where he took the [Mario] Puzo book and cut out the pages and put each one inside a page of his notebook. They’ve now published it, actually, but at the time, us frantically rushing to the photocopier to do 30 pages at a time, was really amazing. It gets to scenes like where Michael kills Sollozzo and the police chief, and Coppola has annotated it and the scene is there in his notes. “One thing I totally realised by the time I finished writing the script - because I had to basically try and pull more information from the book and then make a load of stuff up - was he seriously did get anything from the book that was any good at all and put it in the movie. There was nothing left. There was the odd scene in the ’30s with Don Vito but really he did an amazing job cutting out all the crap and ending up with a masterpiece.” Then, something changed. Coppola pulled out and all of a sudden he turned on the game in the press, saying, “They never asked me if I thought it was a good idea.” And, “I had absolutely nothing to do with the game and I disapprove. I think it’s a misuse of the film.” His beef seems to have been all the action in the game. Action the game needed but the film didn’t have. There are only around 15 minutes of action in the whole Godfather film.“What they do,” Coppola said about the game, “is they use the characters everyone knows and they hire those actors to be there, only to introduce very minor characters, and then for the next hour they shoot and kill each other.” Campbell sighs. “There are only so many car chases or explosions you can duplicate from The Godfather to serve the purposes of a video game. “I don’t know. There may be money involved - I have no idea about that. All I know is he was brought in and he gave us full access to all his facilities. I watched all the tapes of the actors auditioning. I just got to sit in his archives and look at everything related to The Godfather. And then along the way, something political happened.” And it stung. “It matters to me still why Pacino wouldn’t do it, or why Coppola didn’t endorse us.” So, Phil Campbell became an architect. He studied in Oxford - Oxford Brookes - and graduated with a first and a masters, then became a registered architect in 1986, working for a company called Rolfe Judd in London. “I always did the fun stuff,” he says. “I never went on site much, I was terrible on site - I’m terrible at construction - but I always had ideas.” Ideas which turned into bars and restaurants, and led him to a senior designer role on Legoland Windsor. Campbell even pitched a colour-coordinated car park to Disneyland Paris, which required people in certain-coloured cars to park in certain-coloured lots. “It was like an Impressionist painting on all these slowly undulating car parks,” he says. “Of course, everyone said it was bollocks,” he quickly adds, as he tends to. “And let’s face it, it was.” His architecture career was going so well he was offered the chance to take over his dad’s firm, Dalzell and Campbell, in Northern Ireland, but Campbell junior had other plans. Phil Campbell and his girlfriend, Julia, who’d go on to become his wife - also an architect - fancied the look of America. “We were literally sitting on the sofa while I zipped through Teletext - remember that?! I don’t think zipped is the operative word! - and we saw an offer to apply for green cards. We did just that. I entered the Irish Lottery and Julia entered the English Lottery, and we forgot all about it until we heard Julia had got in. We didn’t even talk about it. We just looked at each other and decided to take on the adventure. The move was totally a blind leap of faith.” They moved to America with nothing but the clothes on their backs and two prized Aalto chairs. And 20,000 comics. Campbell was terrifically excited. He was a lifelong fan and could only imagine how impressed his wife would be when she knew who was calling, so as quietly as he could, he called her over. “I was gesticulating to my wife saying, ‘It’s Bowie, it’s Bowie!’” But how to prove it? He had an idea. “I quietly put him on speakerphone so she could hear the man,” he says, and they gathered around the phone. No sound, however, came out. What had happened to David Bowie? What they hadn’t realised was David Bowie wasn’t in a good mood. He had actually phoned to give Phil a bit of a telling off. What they also hadn’t realised was everybody knows when they’ve been put on speakerphone. The silence continued until eventually, Bowie spoke. “Phil, have you put me on speakerphone?” Oh dear, rumbled by your musical idol. Campbell had no choice but to own up. “Yes, David,” he replied, like a guilty schoolboy. I’m sure his wife was very impressed. Campbell laughs about it now, of course, it’s one of the stories he tells, and the truth is, he and Bowie got along famously. They met a long time ago, in the mid-90s, working on Omikron: The Nomad Soul, a David Cage, Quantic Dream game - two relatively unknown names at the time. Campbell was the senior designer and had Cage’s ear, as much as one can, and they needed someone to do the soundtrack to the game. To Campbell, the answer was obvious: Bowie, obviously. But David Cage disagreed. He wanted Bjork, she was bigger at the time, and usually where David Cage is concerned, Cage gets what Cage wants. “He’s an auteur, you know,” Campbell says, “he’s [François] Truffaut. I always wanted to be Hitchcock in that relationship but still.” Somehow, though, Bowie won out, and through a persistent Eidos producer and Bowie’s business manager Bill Zysblat, a meeting was set up. Bowie was to meet Campbell, Cage, and a gaggle of Eidos higher-ups - even the CEO - at Eidos HQ in Wimbledon. And to everybody’s surprise, he showed up. “He watched everything and came back the next week with Iman [his wife] and Reeves Gabrels [Bowie’s musical collaborator of many years],” and agreed to do it. But he had a condition: if he was going to do it, he would do it properly. He would write and record an original album for the game and be in it. I bet their ears nearly fell off. What followed was a Parisian dream for Campbell: two weeks of working with David Bowie every day. “We rented a flat for the duration and David booked into a fancy hotel under an assumed name. He was writing all this stuff, pitching it to us every day. He would turn up at nine, work practically nine to five. It was an unbelievable phase.” They laid the groundwork for the album which would become Hours, “smoked too many of my cigarettes to count”, and came up with an entire soundtrack for the game. (“It wasn’t the greatest album in the world but we’ve always loved it because it filled our world with music.”) Anything Campbell put in front of Bowie, he’d sign. He even tried to push a bit of poetry on Bowie, which he “gently rejected”. “Of course he never told me…” Campbell pauses. “What I really wanted was - you know he was famous for doing that cut-up technique, the [William S.] Burroughs thing, where you cut and paste words together to create sentences? He had a computer program for that which I desperately wanted to get hold of but he refused.” Nevertheless, Campbell, once a boy in the Bowie Fan Club, was now a close friend of the man himself. There was a lovely moment at the Omikron wrap party, in a restaurant near the famous Louvre Museum, where Bowie beckoned Campbell over to sit next to him. “Seconds before,” Campbell says, “all the Eidos big-wigs had been jostling for the spot. But David simply beckoned me over, patted the seat and said, ‘Phil, mate…’”. It’s fondly referred to as ‘awesome Bowie moment number two’. Bowie really threw himself at Omikron - it wasn’t a fleeting involvement. He played two characters in the game and motion-captured “some classic Bowie moves” for in-game concerts. He believed in the game and medium so much he saw it as a platform to reinvent himself. “He wanted to take Bowie into Omikron and leave him there and come out the other side as David Jones,” Campbell says. “He wanted to take his life back and leave Bowie. Bowie would be gone forever.” Think of the two characters he played in the game. One was an omnipresent half-man half-robot called Boz, the sort of character you’d expect Bowie to be, whereas the other character was an 18-year-old starving street singer called… David Jones. “Of course, that didn’t happen,” Campbell says. “In the end, Omikron itself could not stand up to the rigors of being the place where Bowie ended. If we’d have sold more copies I wonder if that whole scenario would have played out, but it just wasn’t important enough.” Bowie and Campbell worked together for two years on Omikron in total, and even after the game wrapped, they continued to see each other. Campbell would travel up to Bowie’s office in New York to pitch him ideas. “Crazy ones.” There was one idea which had come to Campbell after seeing something on the news about space junk - old decommissioned satellites circling Earth forever. “And you could buy these,” he says. “So I suggested to David he could buy these satellites and launch Ziggy from there again. Well it’s obvious, right, that’s roughly where he was from!” Bowie didn’t go for it. There was another idea to make a giant character in Times Square called, wait for it, Bill Board. Campbell can’t even remember what Bowie said about that. But he does remember using interviews with Bowie as a platform to promote some of these ideas, and he does remember an email Bowie sent to him at the time about it. “He simply stated, in his most Warholian fashion, ‘How are you enjoying your fifteen minutes, Phil?’ I wasn’t sure if I should be pleased or not!” Guest list tickets continued for years afterwards but the two men drifted apart. Then, in January 2016, while Campbell was watching the movie Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, the news broke about Bowie’s death. “I still find it hard to believe he’s gone,” he says. Today, he has a pile of signed memorabilia to remember Bowie by, his “prized possessions”, he calls them, and of course he has treasured memories. Which brings us neatly around to ‘awesome Bowie moment number one’. Taking him up on the opportunity of guest list entry years later, Campbell decided to try again to introduce his wife to David Bowie. They went to see him play at the Roseland Ballroom in New York, sitting at the VIP table with Iman “and, man, really lapping it up”. Then they went backstage afterwards to see if they could find him. But they couldn’t. It wasn’t until Bowie’s managers Coco Schwab and Bill Zysblat pointed the Campbells in the right direction they found the room Bowie was schmoozing press in. “We walked into this big room and all the press photographers were there taking photographs, and he was there, meeting and greeting people, and he turned around and saw me coming into the room.” Gulp - would this be another speakerphone moment? “Phil!” Bowie shouted. “And he ran over and he planted a big kiss on my lips, right in front of my wife.” He laughs loudly. “Best moment of my life, mate, I tell you!” So, he volunteered. He went to places like EA and Domark (which would be bought by Eidos, which would be bought by Square Enix) and tested games, and every time, he left a calling card. Literally - he left a resume designed like collectible trading cards. “And somebody fell for it.” Domark fell for it, and he started his own game there called Blackwater. “Here,” Domark told him, “use these new tools, they’ve been developed at Core.” As in, Core Design. As in, Tomb Raider. But Tomb Raider hadn’t been made yet so, for a while, things were peachy. But as Tomb Raider’s star began to rise, things began to change. Suddenly, the tools weren’t for anything but Tomb Raider. “We’re never going to use these tools for anything other than Tomb Raider,” Domark announced, “so we can’t do your project.” The Blackwater team was “trashed” and the project cancelled. But Campbell’s aptitude with the tools wouldn’t go to waste. He was sent to work at Core Design in Derby. “It was like punishment!” But Core Design didn’t want him. Core Design really didn’t want him. “They got me to come over and the first day I was in Derby, the original Tomb Raider team - the game hadn’t shipped yet - they circled me like wolves,” he says. “They refused to let me sit down or go to work because it was theirs - we’re not having anyone else come in. They literally circled me and said, ‘You can’t work here. Nobody else is working on this. It’s ours.’” It wasn’t until operations director Adrian [Smith] stepped in and “saved my life”, Campbell was allowed in. “Adrian calmed them down so I decided to start coming into the office,” he says. “I would go into Core’s offices and work late and build levels, and just build, build, build. And slowly - it’s one of those movie scenes - one by one, they’d look in and show they’re curious. And then they’d play it and say, ‘Oh this sucks,’ and then they’d play it a bit more and go, ‘Oh that’s a good idea.’ And so by the end of it I got nothing but support from them - that was the amazing thing at the end of it - but it was like trial by fire.” Five years, he worked on Tomb Raider, creating, writing and designing expansions and fleshing out Lara Croft as a character and collaborating on comics. However rocky his start at Core Design, working there “taught me almost everything I needed to know”. What pulled him away was the ambitious young French studio Quantic Dream, also under the Eidos umbrella (Domark was bought by Eidos in 1995). Campbell was still technically an Eidos employee while he worked on Omikron: The Nomad Soul, “But I had so much faith in Quantic Dream at that time that I left Eidos to go work with David [Cage],” he says, “because the allure of what he was trying to do was just too interesting.” I’ve just asked Phil Campbell a tricky question and he’s at a loss for words, and that’s a rare thing. But it’s a tough question: “What’s the best idea you’ve ever had?” It’s like knocking on the door of London’s National History Museum and asking for their best dinosaur bone - Campbell’s had thousands of ideas. I can almost hear him flicking through them in his mind, yep-noping them as they pop up. Then he pauses. “Do you remember a game called Fear Effect?” he asks. I pretend I do. “I singularly remember standing on the phone talking to [the game’s makers] and coming up with the notion that the health and all the other systems in the game should be like a fear effect.” But no, that’s not it, he goes back to looking. “I churned out so many ideas into Tomb Raider in the early days,” he suggests. “Every possible level-design trick I could summon. The rolling ball thing, the classic Indy thing they stole and made a Lara thing: I thought ‘Why do we have to limit it to one rolling ball? Why can’t we have a ceiling full of them dropping on you in a weird chess puzzle game?’ And I did that. I always challenged all of the assumptions.” But no, that’s not doing it either. Then, suddenly: “My worst design decision ever? I can tell you that for sure.” The idea is in another Quantic Dream game: Fahrenheit (known as Indigo Prophecy in America), the game Quantic Dream made after Omikron. Again, Campbell was instrumental in the design, but this time he wouldn’t see the game through by virtue of it taking three years, apparently, to find a publisher. “We couldn’t sell the damn game!” he says. It wasn’t until Fahrenheit came out, Campbell realised his worst piece of design. It dawned on him after Godfather senior designer Mike Olsen returned one morning to give his verdict of the game. “Play it, you’ll love it!” Campbell had told him. Olsen’s reaction, however, didn’t tally. “He came in the next day and he was so angry and frustrated,” Campbell says. “And he said, ‘I played this game and it was so shit. I got completely stuck.’ I couldn’t understand why Mike was so upset.” Then it clicked. Olsen had gotten stuck at the place you had to stand still and do nothing - the place with the giant flying bugs. Oh dear. “This was my clever-clever design idea,” Campbell says. “It was supposed to show that you were mad - you were swatting at things that weren’t there.” But doing nothing wasn’t as easy as it sounds. “You’ve got to remember, Mike Olsen is a hardcore gamer. Hardcore,” Campbell emphasises. “He did the whole hand-to-hand system for The Godfather. And of course a hardcore gamer like Mike, there’s only one thing in games he can’t do…” He pauses for a bit of dramatic effect. “…do nothing.” Campbell learned his lesson. “I realised at that time you can be too clever for your own good.” Our conversation meanders after this, while Campbell’s search for his elusive best idea goes on. At one point, we’re talking about The Untouchables film, the one with Kevin Costner in, the really long one. We’re talking about it because Campbell pitched an Untouchables game idea to Paramount. “I’d been so pissed off,” he says. “Every single time I was writing something, it was the hero’s journey, it was rags to riches, it was Ray Liotta pushing through the crowd in Goodfellas and becoming a made man. I wanted to do something where, like with the Scarface game I designed at the time-” Oh, by the way, he made a Scarface mobile game. “You’re Al Pacino, you’re on a mountain of cocaine - not literally - and you’re trying to cling on. I loved that narrative where you’re at the top already. I wanted to be Brando, you know? I wanted to be Robert De Niro playing Al Capone, hitting the guy with the baseball bat in The Untouchables.” The Untouchables game would let you do that, play as characters other than the hero. He’s really proud he got this into Quantic Dream games, he tells me, and as he does, it finally hits him: “The best bit of design I ever did. I’ll tell you know, I remember - have you time for it? “For me, probably the best piece of work I’ve ever done is…” would you believe it? Also in Fahrenheit. “I was responsible for doing the diner scene at the start of Fahrenheit which became the demo. For me, the demo was the perfect little game.” Do you remember it? The game opens with you, the player, murdering a man in a toilet. You weren’t in control when you did it but now you are in control, you have a body to deal with, and you know, because of a split-screen view (“unashamedly” stolen from the TV series 24) there’s a cop in the diner and he’s going to need the toilet real soon (Campbell calls him “living timer”). Sure enough, the cop gets up and walks towards the crime scene. You have to get out… Then the game spins and you’re a detective on your way to the crime scene. But of course, as the player, you already know what’s gone down, even where the murder weapon was thrown. It means you waltz in acting like a proper detective, not some rookie, bumbling around. “There’s nothing worse than a player coming into scene, playing a policeman, and not acting like a policeman,” Campbell says. “Once you stop doing appropriate things, you break the immersion.” In other words, it’s a Bond moment - a term Campbell picked up working on 007. “Bond always had to be Bond,” he says. “The minute he trips on a curb because you built it badly, or he slides off a roof, that breaks the Bond spell.” The spell in the Fahrenheit demo held. It had tension, it had pace, it had immersion and different points of view. “It summed up everything I wanted to do.” Yet, Cage and Campbell went on to work together for many years, Campbell as contracted help. They worked together right up until recently, through Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls. “I did the adaptation,” Campbell explains. “Basically, David would send me wadges of French, translated by a student, and ask me to create all the voices for the characters. It worked really well in Heavy Rain; notwithstanding some of the very bad acting, the good actors’ roles really came across. I got some great write-ups in press on that. “In Beyond: Two Souls…” He pauses, probably because the game wasn’t well received. “It’s funny,” he goes on. “Beyond: Two Souls was supposed to be David Cage’s game-game and it was a beautiful game, great characters, but what neither of us really realised at the time was it had no agency […] you couldn’t die or anything, whereas Heavy Rain had hit that sweet spot where you could lose your main characters and the story could go all over the place.” Evidently, Campbell didn’t mind Cage’s domineering way of working and the two men forged a strong working relationship. “I think I’m one of the only people who’s been able to work well with David over many, many years,” Campbell says. “I did a few more things with David but I lost contact with him around Detroit.” Campbell was brought into EA on the James Bond licence, where he was the creative director on Agent Under Fire (2001) and Everything or Nothing (2003). They weren’t brilliant but they did try to be more than movie tie-ins, bringing original stories to the series. The Godfather, though, was Campbell’s all-consuming work at EA. “The Godfather was and always will be my baby, for better or worse,” he says. “Just going through a four-year process, which is a really long time, hearing that theme music on loop in the studio - I never want to hear it again, forever. But creating a world, creating every single building in that world, every single mission, every single word, was an incredible experience.” But living and breathing The Godfather for four years wore him out. He had mafia coming out of his eyeballs and needed a change. It led to a fateful decision. “I made the stupid mistake at EA of saying, after Godfather, I’m not working on Godfather 2,” he says. “I couldn’t. I just couldn’t face any more Godfather.” He asked to be put back on the Bond team and EA obliged. “So I went back to Bond for about two weeks and then they sold the bloody licence to Activision and I was out of a job, just like that after six years. That was the hardest part.” Nothing had quite landed for him after EA. He suggested a Virtual Me idea to EA while working as a consultant. “It was an idea I had that we could consolidate all of EA’s avatar systems, company-wide,” he says. Imagine having one avatar you used for FIFA and Madden, Battlefield and Apex. “You had a single avatar that had all these guises and shared qualities,” he says. “It was a good idea. It’s just, EA’s a very big organisation…” They worked on Virtual Me for six months, soft-launched it in Poland, “But it really didn’t work,” he says. “It didn’t make it.” Augmented reality and virtual reality came next, through a company Campbell co-created with Irish animation heavyweight Greg Maguire, who’d worked on blockbusters like Harry Potter and Avatar. They, as Inlifesize, had all kinds of ideas. There was an idea for wellness pods. “Imagine the Tardis,” Capbell says, “a Tardis for wellness.” You, surrounded by your medical data. It didn’t catch on. There was an Evil Dead idea Campbell created a gorgeous interactive art book for, to pitch American filmmaker Sam Raimi. It’s got these amazing drawings with cut-out sections that act as windows to the page below, then transform when you flip the page. It’s hard to describe so I’ve included a video to do the job for me. “We never really got the project going the way we wanted,” Campbell says, “but we did ship as a kind of endless runner.” Their biggest bet was on a game called Fairy Magic, an iOS game which used your phone’s GPS and camera to overlay magical creatures in the real world. Sound familiar? “It was totally Pokemon Go without the Pokemon and the monetisation,” Campbell says - and it was released three years earlier. But it didn’t catch on. “We hit too early,” he says. “We ended up making about two bucks a day.” If that wasn’t painful enough, Fairy Magic had once been conceived as a Game of Thrones game, and the licence was a very real possibility in 2011, as Inlifesize was funded by Northern Ireland Screen, the company bringing Game of Thrones to Northern Ireland (a now historic move which transformed the region - “We take it very seriously, our gold and our Game of Thrones.”). But Campbell ditched dragons in favour of faeries and the more family-friendly age rating which came with it. “We turned down Game of Thrones early in the GOT process, which was probably our worst ever mistake.” But what brought Inlifesize to its knees was Doctor Who. “We pitched Doctor Who - we’re all big fans - and what I thought was an awesome AR [augmented reality] Doctor Who game,” Campbell says. “It started in the Tardis and ended up with the Weeping Angels and the Daleks and everything you would expect, and we pitched it for about eight months. We built everything, we did demos, and basically we were told, at the end of the line, that this AR thing, it’s never going to work. ‘Would someone want to do that on the bus?’” Even now, in 2020, people still aren’t convinced about virtual and augmented reality, and Campbell was banging the drum in 2014, when Oculus Rift was still a development kit two years from commercial release. The ideas fell flat and Inlifesize was wound down. It’s at times like these we turn to those we love and so Campbell turned to his wife, who had some motivational words for him. “Go and get a job for fuck’s sake!” she said (Campbell exaggerates for effect) and that’s how he ended up at Zynga. It wasn’t all bad. In fact, for a while, it was brilliant. He was unleashed on all the brands he loved - The Walking Dead, Ghostbusters, Justice League and Batman - and ideas poured from him, earning him the cheesily named Design Rockstar of the Year Award in 2015. “For one year it was glorious,” he says. “But the other two years…” You have to remember, this was Zynga in decline, with three CEOs in three years and a rapidly depleting workforce. One by one, the people around him disappeared. “At one point, I had a whole wing,” he says. “I had a floor at Zynga because they’d been firing so many people I ended up sitting on my own.” But he didn’t sit idly. ‘I know what I’ll do,’ he thought to himself. ‘I’ll decorate.’ So he got out his Sharpie and plastered any surface in sight - and Zynga loved it. “Everybody who visited Zynga would be brought round,” he says, to be impressed by the overt display of creativity before them. But Phil Campbell’s way of working began to fall from favour at Zynga. A more methodical approach was desired. Micro-managers moved in, “and I’m a very hard person to micro-manage”. “The final year put me off the business forever.” So in 2016, fed up, Phil Campbell walked away. But such is the nature of success, I suppose. We don’t hear about the runners up because history celebrates the winners, and for all it promised, Omikron didn’t quite come together, and The Godfather never measured up to the film. But everything Campbell was involved in tried something new. It had new ideas, ambition, guts. The second Godfather game, without him, was empty. To lose that relentless creativity and energy: it’s a great shame. It’s our loss. Unless. Unless Phil Campbell ended up somewhere he was always meant to be. “I run about in my classes and I’m jumping on tables, demonstrating mechanics, doing a lot of shouting and drawing on the wall. For old men like me, just raising your arms above your head is dangerous, but I can’t help it.” Today, Campbell teaches. Four days a week, he’s leaping on tables at either Berkeley City College in San Francisco, or Cogswell in San Jose, inspiring the minds of tomorrow. And he loves it. “I wish I’d started 10 years ago,” he says. And they love him. He has the highest retention rate of any class at Berkeley City College. “Every semester I have one hundred and fifty new names to learn - at my age!” he says. Maybe it’s to do with his lenient marking. “I can’t be bad cop ever,” he says, “it’s ruined my career actually.” Or maybe it’s because he throws comics at students to inspire them. It’s not as though he’s going to run out, he has 25,000 comics at home. Or maybe it’s because having ideas isn’t as easy as it sounds. How many have you had today? I imagine you’ve had at least one idea while reading this piece (it’s long enough). But what did you do with it - swallow it? What good is it to anyone then? “I’ve been known in my time, variously, as a great gushing waterfall and a rusty, leaky tap,” Campbell says. “You get both because what you do is you decide to commit. A lot of people will have these ideas in their head and they’ll never emerge. I say get it out. Seventy per cent of the time it will be OK, thirty per cent, people will think you’re stupid, but, you know.” And he’s developed a few methods over the years to help. “Bodystorming is basically brainstorming using your bodies,” Campbell says. “You have a situation and you all play a character and you bodystorm it - you move around, you communicate, you act, and it helps you sort out problems. It’s really brilliant for level design.” Campbell learnt bodystorming from a guy called Sean Cooper, who used to swear a lot. “When I used to go over and work with Core on Tomb Raider, swearing is just, you know, a casual thing in Britain.” He laughs. “Cooper would come over with a lot of big nasty swears and get everybody’s attention and annoy everybody, but you’d be sitting in a meeting and he would, not angrily [but to demonstrate], flip a chair over and duck behind a desk. He would climb over, he would show what Bond would do physically in any given situation. “It was the best example of bodystorming I’ve ever seen. He’s an incredible guy. It’s like this legacy of game stuff that gets passed down from the earliest games.” “A hidden narrative is what I had to use many, many times in Tomb Raider because I was churning out levels so quickly over a short period of time I had to find a way of not ever being stuck,” he says. “A hidden narrative is taking an established piece of media - it could be a song, a poem, a book, almost anything - and you take that classic structure and set out a beginning, middle and end of a narrative for whatever your designing, let’s say a level, and basically insert Lara Croft into that scenario and keep working it and working it until the hidden narrative disappears. “I based some of Lara’s levels in Egypt on Alice in Wonderland. Right at the end, she’s at the Tea Party, only I created a tea party with all the Egyptian Gods instead of the ones in Alice, and that led me to some more ideas. Or, she goes through the rabbit hole, so I had Lara diving down into… “I based level designs on my back garden. Anything that triggers you and keeps you going,” he says, “because the worst thing to do is to stop.” This is his favourite, and it’s remarkably easy to do. Why, I feel like something of an expert already! The idea of half-remembering struck Campbell while giving a talk he had completely forgotten he had to give. He was just leaving the hotel to go to the airport when an organiser spotted him and said, “Oh, Phil, the room’s over there. If you could just-” Phil interrupted: “What for?” “You’re the keynote speaker,” he was told. “So I walked out and quickly whipped up my slideshow and I had no idea what to say, and the room was packed - they were practically coming out the doors and windows. “So I just started the usual chat and showed a few slides and talked about what, you know, we talked about, in a way, and then I couldn’t remember something and I started talking about fuzzy memory, and I just came up with the phrase ‘half-remember things’. And the place erupted. “It was like one of those moments where you go, ‘I came, I saw…’ and everybody just goes ‘yeahhhhhh’. And it was completely spontaneous. It wasn’t deserved! It just was the way the room was, the atmosphere. Whatever the way it was I said ‘half-remembered’ made people go ‘yeahhhh’. It was like scoring a goal!” Half-remembering is when you can’t quite remember a plot from a film, say, and end up confusing it with another one. By stitching them together, you create something new. It’s the sort of thing we do all the time in dreams, hopping unquestioningly from one thought to another. So get fuzzy, let yourself forget. “Don’t become a Wikipedia,” instructs Campbell. “If you can keep your thinking a little bit fuzzy and you can create links between dreams and reality, just let it roll. It doesn’t matter if it’s real or imagined. It’s stuff, It’s content, it’s ideas.” We snap back to talking about teaching. “I’ve been called the c-word a lot,” he says. I laugh. “That one too, yes,” he goes on, satisfied, “but ‘catalyst’ is the word people use for me. I put ideas together, I get things to work, I share.” He triggers imaginations, it’s what he’s always done. He throws up thoughts for other people to jump in on, pulls people in, bounces off them. And he does it now, coaxing his students into a place where they have no fear sharing their ideas. They rarely sit down. He tries to get them up on their feet, away from books, playing, sharing, collaborating. That’s key, working together. If he’s learned anything in his time in the industry, it’s to crack collaboration early on. “I don’t falter,” he says. “I don’t let people go off and work on their own.” It makes him happy, teaching. He’s content. He’s finally found somewhere his methods and way of working really click. And though he’s not directly in the games development industry, who knows? His effect upon it now may be greater for those he equips to join it. He feels good about that. “It’s a bit of a legacy thing,” he says. “I get paid very little - luckily my wife has a real job. I’ll just keep teaching until I drop, probably. I just love passing it on.” If he has a regret, it’s not taking any pictures with Brando. He couldn’t, he wasn’t allowed, nor would Brando sign anything. But he has his memories of Brando, Bowie and more. How many people can wheel out the kind of stories he can? “I just look back on a ton of memories and think how lucky I was to be in the right room at the right time,” he says. There’s still architecture - he picked it because he could do it when he was 80, remember - and it never really left him. It’s why, when he was making The Godfather, his virtual New York had a ludicrous 200 landmarks. He knew them all but how many can you name? The Rockefeller Center, The Empire State Building, Central Park, um, the Friends apartment? It wasn’t until an EA executive came to ask members of the team the same question in order to prove a point - they averaged around five or six - Campbell finally conceded. He still plays The Godfather with his students, you know, and finds unexpected pleasure in it. “What was great about playing The Godfather was not playing the missions,” he says. “The joy of Godfather was just starting a rumble in the middle of town. Not in the design plan, not intended, but a true joy to play. That’s what I look for in games.” He dabbles in a bit of architectural work too. “I still consult,” he says. “I consulted on the Titanic museum in Belfast. But it’s all very casual. My wife is a real architect.” They collaborated recently (he credits her with all the work) on a very personal project. It’s the reason he suddenly breaks off during our conversation to talk to an engineer. I hear the word “elevator” and I’m just about to ask when he beats me to it. “Sorry about that, Bertie,” he says, “we just built a new house, finally, after all these years, and I’m standing here looking at the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s certainly beautiful here this morning.” More specifically, he’s standing in his rooftop garden overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge, and he has a six-story bookcase running up the stairs. Downstairs, on the bottom two floors, there’s an apartment stuffed with “everything my wife didn’t want in the house”, all his gaming paraphernalia, and they rent it out on Airbnb. “We just started,” he says. “It’s like a pop culture museum.” It might not have panned out the way he expected, then, but it panned out pretty nicely in the end. “It’s Retirement House,” he says. Then he changes his mind. “That sounds bad.” He thinks for a moment longer and with a laugh hits upon something better. He says, “This is a house to befit someone who’s not quite famous.” I have ideas, too. No, really! They pop up all the time. But I am in no way as disciplined and determined in getting them down. That’s his mastery. No doubt he’s already off concocting an idea to delight or torment his students with. That’s nice. I’d like him as my teacher. I think of it as his final form. But he wouldn’t be there had he not gone round the houses learning his trade, and as the cliched old saying goes, we learn more from our mistakes than we do our successes. It’s changed my mind about what this story is. Someone asked me this last night and I struggled to answer - never a good sign when you’ve spent so long on something, let me tell you! It was once, simply, the amazing stories of a man I’d never heard about, and maybe it still is. I hope you’ve enjoyed them. But that feels a bit disingenuous, too, a bit thin. It implies, I think, he’s never found success, and I don’t think that’s right. Success irks me, because what does it actually mean? Does success mean you’ve attained the highest honour in our society? If it does, what is that - fame and fortune? Is that really all it is? I don’t like to think so. It reminds me of when I used to take my son to ninja lessons, because that’s what parents in Brighton do, and of something they taught there. It always stuck in my head. They taught that the highest honour you can attain is to teach. Not to become a great warrior, famed and acclaimed, but to learn so much you will one day have the great honour of passing it on. That, I like. Phil Campbell, grandmaster, talking at a hundred miles an hour and cracking jokes. Passing it on.